The Struggle of the Laissez-Faire Economy at the End of Republican Dynasties (Economic Editorial)

Article by: Rhett Brady I Staff Writer, BCS Chronicle

What You Need To Know:

America followed the laissez-faire economic system in the 1920s and 1980s.

The Republican party controlled the presidency for 12 years in each time period, and promoted tax cuts and less regulation.

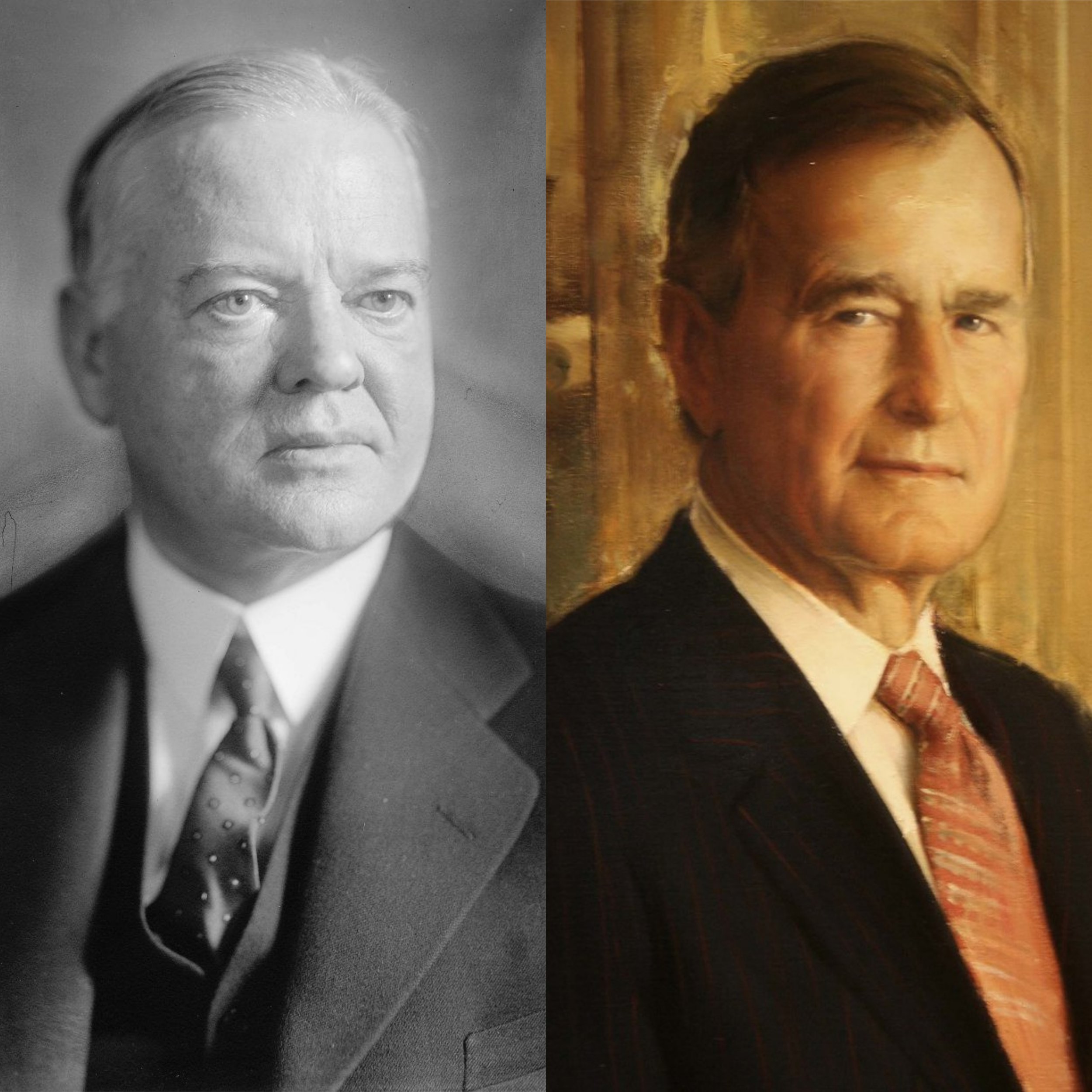

President’s Herbert Hoover and George H.W. Bush tried to follow the economic polices of their predecessors.

The American economy both crashed under their administrations, and they were attributed to their policy failure.

Both men were flawed in their economic policies, but one can see that they cared for the American public.

The 1920s are remembered for the Republican dominance of the presidency. Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover were the leaders of the country throughout the 1920s and the early 1930s. All three presidents led America through a prosperous decade of economic growth, new cultural trends, rapid implementation of new technology, and a “return to normalcy” (Harding, 1920).

Republican leadership has still been commonplace since the loss of Hoover in the 1932 election, with seven Republican presidents elected after WWII (The White House). Consecutive party power in the presidency is rare in the United States, with the country flipping between parties every four or eight years. However, consecutive Republican presidents also occurred in the 1980s with two presidents. Ronald Reagan served as president from 1981 to 1989, and his vice president George Bush Sr served as president from 1989 to 1993. However, Bush and Hoover, two one-term presidents, are the most similar among these five presidents.

This work seeks to examine the similarities between the administrations, with some context from the others, how modern conservatism has been influenced by the economic policies of the 1920s, how large tax cuts helped lead to economic recession in each period, and the similar economic rhetoric of the Hoover and Bush administrations that made them fall out of favor with Americans.

Presidential portraits of Hoover and Bush respectively.

Each of the 1920s presidential administrations can be categorized by historic tax cuts, with a tax hike at the start of Hoover’s. The Revenue Acts of 1921, 1924, and 1926 are attributed to the secretary of the treasury Andrew Mellon, who served under Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover. Each of the “tax cuts allowed the U.S. economy to grow rapidly during the mid and late‐1920s. Between 1922 and 1929, real gross national product grew at an annual average rate of 4.7 percent and the unemployment rate fell from 6.7 percent to 3.2 percent. The Mellon tax cuts restored incentives to work, save, and invest, and discouraged the use of tax shelters,” (de Rugy, 2003).

Hoover, a believer in the laissez-faire economy, wanted to keep the low taxes and continue the ever-growing economy of the two previous administrations. Hoover “believed an economy based on capitalism would self-correct. He felt that economic assistance would make people stop working. He believed business prosperity would trickle down to the average person” (Amadeo, 2021). Buying stocks based on margin, a lack of antitrust legislation for businesses, and hardly any regulation in the market contributed to the start of the Great Depression at the beginning of Hoover’s presidency. In response to the horrid depression, Hoover was forced to raise taxes to combat inflation. However, due to Hoover’s insistence on keeping a balanced federal budget and lack of federal spending, “GDP growth fell 12.9% and unemployment was 23.6%,” (Amadeo, 2021).

Hoover’s perceived lack of compassion and seemingly effortless attempt to control the economy led to his loss against Franklin Roosevelt in the next election. History often can happen in patterns, and the principle of 1920s economic policies carried over to 1980s Republican leadership. The course of events, while not as severe as the Great Depression, are similar enough to see a correlation.

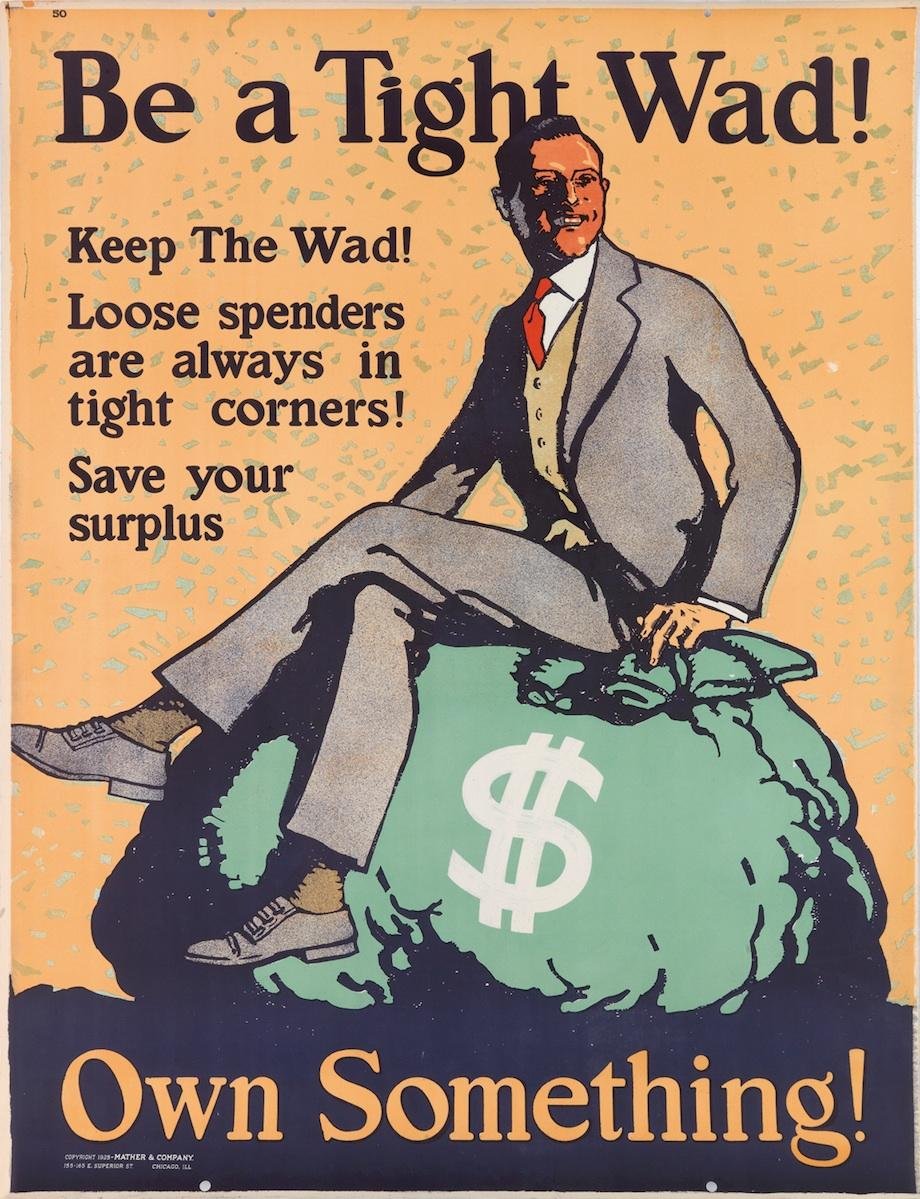

1920s propaganda poster illustrating the booming economy and high wages of the American public.

After four years of a lackluster economy, high inflation, and the Iranian hostage crisis, incumbent President Jimmy Carter lost to the charismatic Republican nominee. Former actor, and governor of California, Ronald Reagan. Reagan’s economic policies were referred to as “voodoo economics'' by who would become his vice president, George Bush. With Reagan's election, the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 was signed into law. It’s one of the largest tax cuts in American history. Estate, corporate, capital gain, marital, and individual were all lowered. This act of legislation very much echoed the laissez-faire economic system of the 1920s, a system that Reagan himself said that he wanted to return to.

After eight years of lower taxes, higher government budgets, and a higher GDP, even with Black Monday in 1987, Reagan was succeeded by his sitting vice president. While the circumstances were different for Bush’s recession than Hoover’s, Bush shot himself in the foot with a promise he made. In keeping with the policies of his predecessor, along with the inspirations from 1920s America, Bush said “read my lips: no new taxes.”

Carl E. Walsh, a professor of Economics at the University of California, Santa Cruz said in his economic review, “Pessimistic consumers, the debt accumulations of the 1980s, the jump in oil prices after Iraq invaded Kuwait, a credit crunch induced by overzealous banking regulators, and attempts by the Federal Reserve to lower the rate of inflation all have been cited as causes for the recession,” (Walsh, 1993). It all sounds so familiar, yet just in a different time with different circumstances. Bush’s one line might have been what slandered his image in the public eye when he passed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, raising taxes. However, there is always more to the story. Bush’s rhetoric, however, was not the first of its kind. One can look back 60 years before to a predecessor to this.

“Norman Schwarzkopf, Jr. and President George H. W. Bush visiting troops during the Gulf War.” (Public Domain)

“While the crash only took place six months ago, I am convinced we have now passed the worst and with continued unity of effort, we shall rapidly recover. There is one certainty of the future of a people of the resources, intelligence, and character of the people of the United States—that is, prosperity,” (1930). Hoover throughout the Great Depression was known for his optimistic rhetoric directed toward the suffering and hungry American public. His optimism for the future of the country, while not playing an active government role because of his small-government beliefs, began to rub people the wrong way after a few years. With “Hoover’s view regarding the relationship between economic performance and collective belief suggests a firm link between economics and presidential rhetoric… Hoover’s initial response to these early calls for rhetorical leadership was to ignore them… The charge of failure, though, would soon move well beyond Hoover’s rhetorical (in)abilities; it would extend to his presidency as a whole. Failure, though, always requires a benchmark, a baseline of comparison—and Hoover’s benchmark has usually been the Roosevelt administration,” (Houck, 2000).

Hoover, Bush, and their respective predecessors carried the ideology of laissez-faire economics with little government regulation, and although Bush had a much tighter grip on the country than Hoover, their rhetoric is why the American public turned on them. However, discounting Hoover as a human should not be taken in with his economic policies.

A political cartoon showcasing how the American public felt about Hoover optimism and prosperity.

Reflecting on Hoover’s presidency, Nicholas Lemann said, “If you asked people, in the abstract, whether they’d rather have a President who was a superbly charming professional politician or one who had come from nothing, built a successful business, and accomplished astonishing feats of altruism, they would probably choose the latter. We think that we don’t need politicians; we even think that we’d be better off without them. The truth is that in a democracy, especially during a national emergency, they’re the only people who can get things done,” (Lemann, 2017).

President Hoover with President-elect Franklin Roosevelt in the Presidential automobile. Roosevelt was voted in as the man to “get things done”. (Public Domain)

Hoover often falls into the category of failed American presidents, but his humanitarian efforts and personal integrity should not be overlooked. Optimism in politics seems to be a lost art in modern America, and while the way Hoover went about the Great Depression likely was not the best course of action, he seemed to deeply care about America and Americans in his heart. He was coming from the prosperous 1920s America, and he wanted to keep the prosperity going the best way he could. His legacy and life before and after the presidency are more well known than his presidential activities. “Herbert Hoover was a talented, complex man whose life has too often been pigeonholed as that of a failed president who passively allowed the Great Depression to deepen…He established the distinguished Hoover Institution at his alma mater of Stanford University, which continues to do fine work to this day… He remained a humble and generous philanthropist, ultimately giving away over half of his income from business profits,” (Fund, 2016). Hoover is one of only two presidents to donate his presidential salary as well. His generosity is also associated with his comparison of this piece, but the latter has a better historical reputation.

Reflecting on Bush’s presidency, Stephen Knott said, “George Herbert Walker Bush came into the presidency as one of the most qualified candidates to assume the office. He had a long career in both domestic politics and foreign affairs, knew the government bureaucracy, and had eight years of hands-on training as vice president…Bush had a conservative nature and was uncomfortable with bold, dramatic change, preferring stability and calm. These characteristics helped him lead the United States through a period of geopolitical transition,” (Knott, 2020).

Being comfortable with how things are is a good way of describing Bush’s presidency. While the war and recession hurt his reputation while he was in office, his retrospective view by Americans, especially in comparison to his son, has helped his legacy. No president is perfect, but Bush’s commitment to being an American serving America is admirable. Circumstances beyond his control, made him lose reelection, like Hoover. They’re two complex figures, but it’s hard to believe they haven’t been compared to each other in a historical context.

Photo of President George H.W. Bush in the oval office on his final day as the President of the United States.

Two administrations that were 60 years apart, and most people would likely not think there would be much in common. The 1920s and the 1980s economy were categorized by low taxes, hands-off government, large government budgets, and presidents that fell out of favor with the American public due to circumstances not necessarily created by the fault of their decisions. The Great Depression and the optimism of the 1920s can serve as a cautionary tale for future economic prosperity, and while the 1990 recession wasn’t as drastic as the depression, the same type of thinking helped contribute to the cause. The 1980s and early 1990s took a lot of inspiration from the 20s, and to see the 20s policies and thinking come back in the near future is likely to happen as well. Only time will tell to see what happens. Until then, reflection on what was good and what was bad is all that we can do as Americans to prepare for the future of our economy.

1920s era political cartoon criticizing laissez-faire capitalism and big business practices.

Works Cited in Order of Appearance:

Barela, Nova. “‘A Return to Normalcy’: How a Campaign Slogan Became Part of Our Pandemic Lexicon.” Reference, IAC Publishing, 22 Dec. 2021, https://www.reference.com/history/return-to-normalcy-origins.

“Presidents.” The White House, The United States Government, 16 Feb. 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/.

“Laissez-Faire Leadership Style (Quick) (Explained): Leadership Analysis.” BuNeden, 19 Feb. 2021, https://buneden.com/en/what-is-laissez-faire-leadership-style/.

de Rugy, Veronica. “1920s Income Tax Cuts Sparked Economic Growth and Raised Federal Revenues.” Cato.org, Cato Institute, 4 Mar. 2003, https://www.cato.org/commentary/1920s-income-tax-cuts-sparked-economic-growth-raised-federal-revenues#

Amadeo, Kimberly. “President Herbert Hoover's Economic Policies.” The Balance, Dotdash Meredith, 6 Dec. 2021, https://www.thebalance.com/president-hoovers-economic-policies-4583019.

Rostenkowski, Dan. “H.R.4242 - 97th Congress (1981-1982): Economic Recovery ...” Congress.gov, The United States Government, 13 Aug. 1981, https://www.congress.gov/bill/97th-congress/house-bill/4242.

Walsh, Carl E. “What Caused the 1990-1991 Recession?” Economic Review- Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, vol. 2, 1993, pp. 1–17.

Panetta, Leon. “H.R.5835 - 101st Congress (1989-1990): Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990.” Congress.gov, The United States Government, 15 Oct. 1990, https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/house-bill/5835.

“Oh Yeah?: Herbert Hoover Predicts Prosperity.” HISTORY MATTERS - The U.S. Survey Course on the Web, http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5063/.

Houck, Davis W. “Rhetoric as Currency: Herbert Hoover and the 1929 Stock Market Crash.” Rhetoric & Public Affairs, vol. 3, no. 2, 2000, pp. 155–181., https://doi.org/10.1353/rap.2010.0156.

Lemann, Nicholas. “Hating on Herbert Hoover.” The New Yorker, 16 Oct. 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/10/23/hating-on-herbert-hoover. Accessed 28 Apr. 2022.

Fund, John. “John Fund: Herbert Hoover Misunderstood.” Newsmax, Newsmax Media, Inc. Newsmax Media, Inc., 3 Oct. 2016, https://www.newsmax.com/Newsfront/Herbert-Hoover-Misunderstood/2016/10/03/id/751349/.

Reporter, Staff. “Meet Other Presidents Who Donated Their Salaries to Charity.” Independent Online, IOL | News That Connects South Africans, 24 May 2018, https://www.iol.co.za/business-report/economy/meet-other-presidents-who-donated-their-salaries-to-charity-15137919.

Knott, Stephen. “George H. W. Bush: Impact and Legacy.” Miller Center, 14 Aug. 2020, https://millercenter.org/president/bush/impact-and-legacy.